I recently dusted off one of my Hyperion/Java flights of fancy the other week: HUMA. HUMA is a tool for scanning a cube and finding which members have no data associated with them at all. As I mentioned in the post talking about some performance tweaks, HUMA scans every single cell in an entire cube to determine what is empty.

One of the reasons I put HUMA on the self for a while is that in a program that does this, there’s a lot that can go wrong to cause the program to fail or run so long that the sun goes supernova before the program finishes. If you were lucky then you’d get a list of members that you could put on the chopping block. If you’re lucky it’s even a member in a dense dimension, whose removal might just increase your block density ever so slightly.

That all being said, let me just say up front that maybe there’s not a lot to be gained from doing this. Maybe the real solution is to buy some nice fast SSDs for your server, or increase the cache size, or check out that fancy new ASO Planning stuff, or whatever. Let me just say upfront that I get that. Nevertheless, this tool exists and if you’re the type of administrator who looks for any edge you can get, well, then maybe you’re one of the dozens of masochists people that have already downloaded this thing.

So, for the curious: how do you and how does HUMA scan an entire cube with a kajillion possible data cells? Glad you asked…

Step 1 – Read the outline

The first thing that HUMA does is read the outline for the list of stored members in each dimension. HUMA also pays attention to which dimensions are sparse and which are dense.

Step 2 – Build a virtual grid with every single cell combination

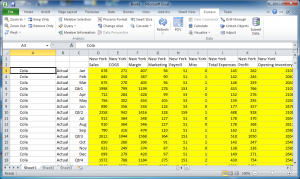

Imagine you’re in Smart View and you are drilling around Sample/Basic. You drill to the bottom of each dimension, and now there is nothing in your POV – it’s just rows and columns as far as the eye can see. You’d have something like this:

In practice, even a barely non-trivial combination of members from multiple dimensions results in a grid that is gigantic – and too big to store in memory all at once. HUMA doesn’t actually generate this grid in memory, thankfully. It generates (incredibly quickly) the member combinations for any place in the grid. Hence why it’s a virtual grid. From here the problem is actually kind of simple sounding: just check all the cells. Before we do that, let’s come back to why we paid attention to dense and sparse:

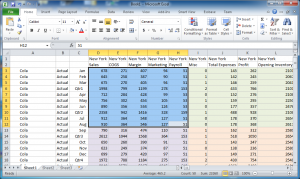

A single row is highlighted: given columns A-C representing sparse dimensions, then the highlighted row represents the entirety of a single block.

Spare dimensions are on the left, dense dimensions are on the top. So you can see that the highlighted row in the above screenshot corresponds to a data block (in a BSO database). The data is strategically laid out this way so that to the extent possible we will be retrieving data against the same blocks over and over, giving the Essbase engine a chance to leave those in memory and serve them up faster.

Step 3 – Retrieve sub-grids

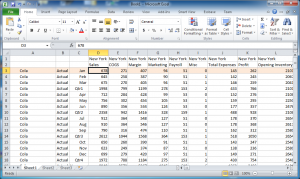

We can’t, obviously, just pull back all the data at once… we need to iterate through it. For technically reasons we also need to limit the number of cells we pull back at once, and we have a maximum number of columns (for Java API purposes) of 256. We might want to set the max cells per retrieve though. So let’s say that’s about 50 cells. We’d then be retrieving sub-grids roughly shaped like this:

A fully expanded grid with different sub-grids of data represented. The top left starts out as grid 1, then moves right to grid 2 and keeps moving right. The next row picks up at theoretical sub-grid number 24.

See that the first grid is one, then to the right (in the same “hot” blocks) is 2, and then so on through to the right side such that the next grid down in this case happens to be 24, then 25, and so on. Even if we just retrieved (or tried to retrieve) all of these grids, it would still take a considerable amount of time. So there’s one more trick up HUMA’s sleeves: quick member elimination. Let’s look at the data in grid 1:

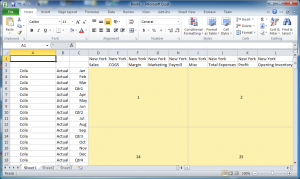

Step 4 – Analyze data and reconfigure search space

We’ve found data for such member combinations as Cola, Actual, New York, and so on. We can now remove these from consideration in the search. HUMA knows that it no longer has to ever check any of those members. Because of it’s extremely fast grid regeneration/iteration, it does this automatically and shrinks the search space by removing those members. This can speed things up incredibly. If you watch the [at the moment very verbose] HUMA output, you’ll see some debugging information about how many grids there are, and as members are found, this number gets recomputed.

HUMA will finish in one of two ways: it eliminates every member from consideration for being unused and it quits, indicating as much, or two, it finishes and it reports back all of the unused members. I guess there’s a third option, which is that HUMA crashes. Actually, HUMA itself won’t crash, but the most likely issue you’ll run into is port exhaustion, in which case you’ll want to increase the milliseconds between retrieves and try again (or just increase the number of ports on the server, as indicated in the help).

That, in a nutshell, is how HUMA operates. This time around, performance is off the charts compared to what the first version was, so that’s cool. This program is available from the Downloads site. This is still a very rough program but please feel free to share your feedback and experiences.